By Howard Gillette

In the twenty years since his landmark book, The New American Ghetto, appeared, the New York-based photographer Camilo Jose Vergara’s role in bringing the face of inner city life to wide public attention has brought him considerable acclaim, including selection as a MacArthur “genius” fellow. As MARCH’s first affiliated scholar in the early part of this century, Vergara produced, with generous support from the Ford Foundation, another ground-breaking contribution, the Invincible Cities web site.

Launched in connection with publication of my 2005 book, Camden After the Fall, “Invincible Cities” tracked changes in Camden’s landscape over a thirty year period. With the Ford Foundation’s encouragement, Vergara added a similar city, Richmond, California, which he had not previously visited. Subsequently, he added photographs of Harlem to the web site he had been taking for years. Together we introduced the Harlem portion of the site at a public program at the City Museum of New York.

Located at the edge of the neighborhood, the museum drew a racially and ethnically diverse crowd that evening, reflecting recent changes in Harlem that have caused some unease about the future prospects of an area long known as the “capital of black America” as it has been touched by gentrification.

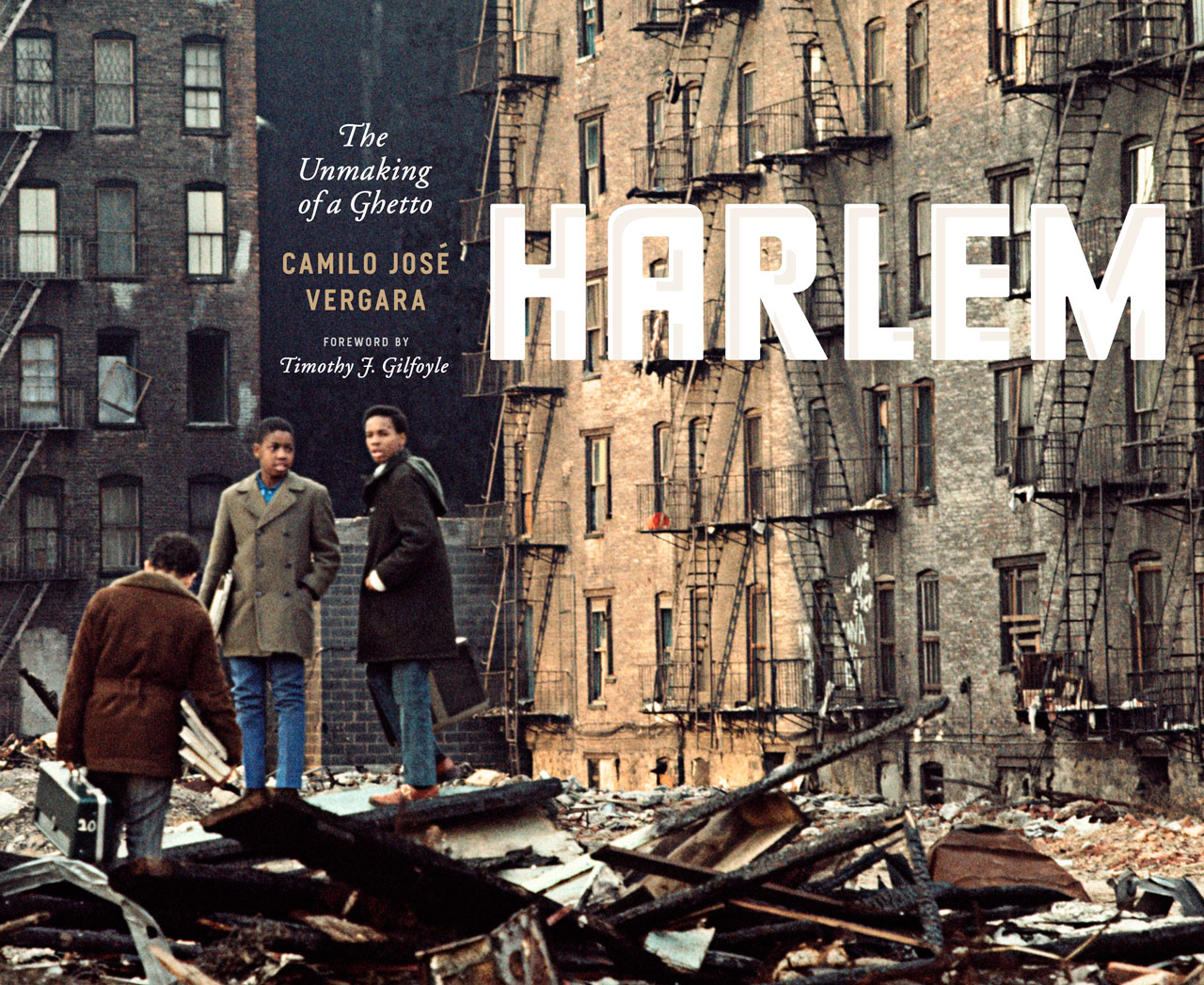

Vergara’s visually stunning book, Harlem: The Unmaking of a Ghetto, begins to address that phenomenon, even as it builds on the Invincible Cities website to employ documentary techniques that distinguished his earlier publications.

The new book is not exactly a bookend to Making of a Ghetto. Many of the signs of ghetto life, most notably physical decay and social disorder, appear in Vergara’s account of Harlem. But there are also signs of transformation, some of them stunning.

Using the technique he has returned to repeatedly, of photographing the same building over time, Vergara documents a decided movement toward upscaling “the hood.” The Purple Manor jazz club, at 65 E 125th Street, for instance, undergoes a number of changes between 1997 and 2011, converting in 2007 to a Sleepy’s mattress store before changing once again to a storefront church.

Other signs of Harlem’s roots in the Great Migration from the South simply disappear, as did the Carolina Meat and Vegetable Market, photographed in 1970.

The invasion of franchise activity is sometimes coupled with efforts to acknowledge and respect the existing community, Vergara reports, as a newly arrived Applebee’s showcases local history by posting images of figures historically linked with Harlem: Gordon Parks, W.E.B. DuBois, Billie Holliday and Muhammad Ali. The contrast between indigenous places and chains remains in Vergara’s own photographs, however, in photos of McDonald’s at East 125th Street and Lexington and Jimbo’s Hamburger Palace several blocks away at West 124th and Malcolm X Boulevard, both from 2011 (60-61). Although McDonald customers sit before a mural of a number of Harlem jazz musicians, they seem not nearly as comfortably at home as the couple at Jimmy’s, a local favorite for years whose own food–described by Vergara as greasy and tasty—could never be confused with MacDonald’s.

Vergara’s first Harlem photographs date before his training in sociology at Columbia between 1973 and 1976. After that experience, Vergara reports in Harlem, he shifted his focus from people to buildings, and this collection reflects that decision. A number of the photographs are shot from tall buildings, a means of establishing context for individual structures below. There, he returns frequently to the same spot, sometimes demonstrating subtle shifts of use and condition. The contrast with images drawn from Vergara’s early work is striking. The city, not the individual has become the focus.

So stunning are the early photographs of individuals, readers might regret the shift to another, more overtly documentary style. But in spite of that shift in emphasis, people remain central to Vergara’s account, their distinctiveness and their humanity jumping from the page.

Vergara breaks his book into a number of discreet sections, choosing to highlight certain phenomenon central to the place. Aside from commercial structures, churches play a central role, as do parades and other forms of memorialization. A sense of history is always present in the text and frequently manifests in the photographs. Indeed, Vergara sees his role in serving as an “archivist of decline,” leaving an unparalleled visual record for future historians to mine.

No whites appear in the volume, despite their growing number as residents of Harlem, until a late section of the book, on tourism. There they join Japanese and other tourists clicking their own picture souvenirs of this historic place. Tourism has become a big business in Harlem. But whites aren’t the only ones visiting, Vergara notes, as he describes black suburban teenagers attending performances at the restored Apollo Theatre. Also included is a photograph of the black mayor of Irvington, New Jersey, posing with colleagues before the Rev. Al Sharpton’s headquarters on West 145th Street in 2012.

The vitality, dignity, and flair of Vergara’s subjects give him hope about Harlem’s future. He recognizes the sense of loss to long-timers of “down home” places, many of which he has recorded. At the same time, a Chilean by birth himself, he takes pride in the area’s movement to multiculturalism. Despite a tendency to make Harlem a “museum city,” he suggests African American culture and history “are still among the strongest and most persistent forces shaping Harlem today.”

How the new mix of people and economic forces blends in future years remains to be seen. But for those who will look back, they can credit Vergara for giving them so many tangible signs of what has made this place special over time.

Howard Gillette is a founder and past director of the Mid-Atlantic Regional Center for the Humanities and Co-editor of the on-line Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia.