By Matthew B. Gilmore

Thirty years after its foundation, the D.C. Office of Public Records (a.k.a. DC Archives) struggles to preserve the records of the District of Columbia government. The situation is not new. In 1905, the Evening Star wrote “Probably many residents of Washington do not know where the archives of the District are to be found.” The Star noted the records were stored in a fire proof vault in a building used as the armory by students of the Business High School on 1st St NW between B and C Streets. “It is not a pleasant place to loaf in, for the vault is exceedingly crowded with many stands of shelves containing the dusty books and file cases and the smell of aged things pervades the close atmosphere.” (October 1, 1905). At that point, the records had been collected and stored in that vault for twenty years. Ultimately those records would end up in the National Archives, founded in 1934, where they remain to this day. The government of the District of Columbia has never had a robust archival and records management infrastructure. For nearly a hundred years, before the granting of home rule, the District was administered, in some ways, as an agency of the federal government. Records of the pre-home rule government of the District are housed at the National Archives (with some councilmember archival collections at George Washington University and the DC Public Library).

In 1985, Dr. Philip Woodworth Ogilvie (an experienced zoo director and Democratic Party volunteer) successfully fought for the establishment of an independent archival and record management system, persuading the then-mayor Marion Barry to support it. Council passed “The Public Records Management Act of 1985 (DC Law 6-19),” which Mayor Barry signed on June 10, 1985. The Office of Public Records Management, Archival Administration and Library of Government Information (Office of Public Records) was established in the Office of the Secretary on February 11, 1986, by Mayor’s Order 86-28.

The effort to create the local archives dates from 1953, under the old commissioner form of government, but by 1982 it had petered out. In 1983, the city commissioned James B. Rhoads, the former archivist of the United States, to survey District records and make recommendations for their preservation and use. [The official records of the District of Columbia: Present status and opportunities for improvement and Public records and private papers in the District of Columbia: Prepared for the District of Columbia Historical Records Advisory Board: a report with recommendations]. Last year, after receiving his report, the City Council enacted legislation creating the city agency.

It will be headed by Philip W. Ogilvie, in my view the perfect choice for the job — a scholarly, low-key man devoted to the task who is close enough to the mayor to ensure support for the mission. Now heading a staff of seven, he said he regards the new task as “truly exciting.” His office will soon be moved to the Recorder of Deeds Building, Sixth and D streets NW. [Ogilvie directed the archives and records center until 1998 and died in 2002].

Space for the archives was ultimately found in an old stable in Shaw at Naylor Court—a building strong enough to support the weight of the records to be stored. Staffing was found too, with Dr. Ogilvie as the head of the public records office. Dorothy Provine moved from the National Archives where she’d overseen D.C. records. Larry Baume came from the Columbia Historical Society. Names familiar to many of us, but now elsewhere. And there were more. The promise of those early days dissipated. Rhoads’ reports can still be found in several historical collections.

The 1990s saw a serious financial crisis in the District and many agencies saw serious budget cuts. The public library faced serious cuts and struggled to avoid branch closures. The public library had a public constituency which the Archives lacked and the archives staffing continued to shrink. Elissa Silverman in “Past Mistakes: The D.C. Archives says just as much about the city’s present as its past” in the January 21, 2000 Washington City Paper told much of the sad story of the underfunded institution.

Soon after opening at Naylor Court in 1990, the archives became a casualty of the District’s fiscal crisis. The staff of about 12 and budget of $550,000 have shriveled to one-third of those numbers. Though news accounts of contemporary Washington stress the city’s revival, the archives remains a victim of the not-so-distant past.

If historic preservation is key to understanding a city’s past and future, D.C. might run the risk of municipal Alzheimer’s pretty soon. For years, the federal government treated the District–and its records–as it did any other federal agency. D.C.’s records sat quietly on the monumental shelves of the National Archives, home to the U.S. Constitution and the Declaration of Independence.

Home rule changed all that. Freed from the federal yoke, the city got the right to liberate its records from the nooks and crannies between 1962 Commerce Department budget-planning session notes and the 1981 Alexander Haig birthday party guest list. But it also acquired the responsibility to keep its mementos in order. That’s the part the city hasn’t quite worked out yet.

“A very important expression of the city’s independence is to control its own records,” says Philip W. Ogilvie, D.C.’s former director of public records, who now works as a senior associate at George Washington University’s Institute of Tourism Studies. In 1982, Ivanhoe Donaldson, a close adviser to Mayor Marion Barry, asked Ogilvie–an eager Barry campaign worker and staffer–to examine the city’s records and archives.

Interest in preservation of records suffered; the State Historical Records Advisory Board (established in 1984 to coordinate with and receive grant funding from the National Historical Publications Records Commission), was abolished in 1998, was reestablished in 2002, but only received appointments sporadically. It’s unclear if it is still active. By 2003 Sewell Chan would write in the Washington Post “City’s Records Center Compiles a History of Neglect” (December 4, 2003).

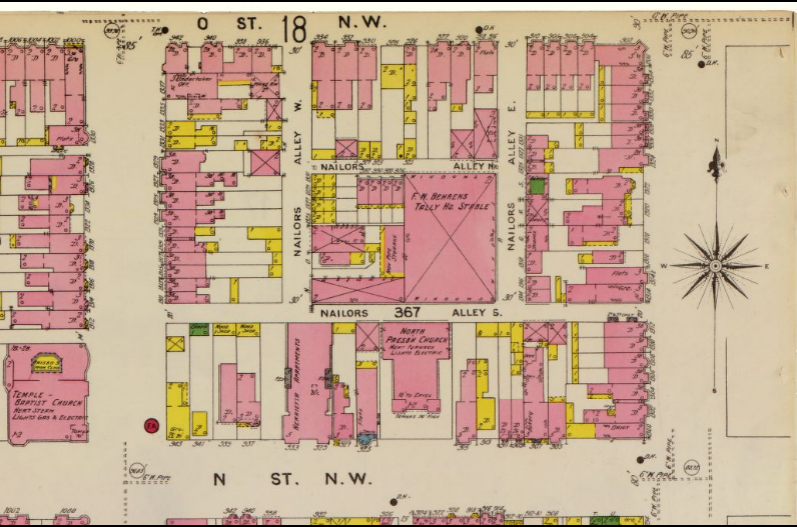

There was no money to buy or construct a building, so Ogilvie surveyed city-owned properties, including vacant school buildings and a former funeral home. None was sturdy enough to support the immense weight of tons of records — except for a forlorn building on one of the District’s oldest surviving alleyways, a narrow corridor nestled within the block bounded by Ninth, 10th, N and O streets NW in Shaw.

“Here was this fortress of a horse barn on Naylor Court, with thick, thick walls,” recalled Lucie A. Ogilvie, his widow. “He was always going into neighborhoods that scared the living bejeebers out of me. He loved it down there. The mechanics in the alley were his friends, the drug dealers and the prostitutes knew him, and they all loved him.”

The building that would house the city’s records had a lively history of its own. Designed by Diller B. Groff, the red-brick stable — 95 by 105 feet with nine bay door openings — was built in 1883 at a cost of $5,000 and transferred to the District’s ownership in 1905.

For a number of years other institutions and organizations, such as the public library and the Historical Society, have wished away jurisdictional issues and proposed taking over portions of the Archives’ functions and/or collections. The Archives is a part of the executive branch and reports to the Secretary of the District (who until recently reported directly to the Mayor). The public library is an independent agency under an appointed board. The Historical Society is a private entity. Contracting out archival and/or records management functions to either would be fraught with political, jurisdictional, and financial difficulty. Another major obstacle has been a lack of funding; if the government couldn’t find funds to staff and support the Archives internally, the likelihood contracting out be better funded is slim.

The concerns about the underfunding of, and lack of public access to records at, the DC Archives (and issues facing preservation, funding, and access issues at much of the constellation of historical/archival non-federal institutions) has not been neglected but raised a number of times at the Annual Conference on D.C. Historical Studies in 2005, a follow-up in 2006, 2010, and 2014.

Successful preservation of threatened DC Department of Transportation photographs spearheaded by the indefatigable Bill Rice has been an encouraging development. Most recently a grass-roots lobbying group has organized itself as the Friends of the DC Archives. A variety of interested folk and stakeholders gathered in April 2014 and organized impromptu. The group has been active lobbying ever since. The June issue of the local InTowner neighborhood newspaper reported on the forum held May 21, 2015 by the Friends of the DC Archives group with the cooperation of the Office of the Secretary of the District.

From that forum the stated goal for the Office of the Secretary is to develop a state of the art, multi-functional facility, to address historical community concerns and archival needs (including a climate-controlled storage facility, researcher space, and museum exhibit space). The Secretary’s office has engaged stakeholders, determined technical requirements, and established and fostered close partnerships with the National Archives and the Smithsonian, leveraging the tremendous resources and expertise on historical cultural resources in the D.C. area. Office staff toured NARA facilities, including preservation labs. The Office next will review retention policies and schedules.

Secretary Lauren C. Vaughan says that the Bowser Administration has opened the search for a new Public Records Administrator; her office has begun the vetting and interviewing process. Much of the discussion at the forum served as a basic orientation to the issues of archives and records management in the District of Columbia and dispensing of simplistic ideas of simply combining disparate organizations and functions. A welter of institutions hold jurisdiction over records of historical interest in the District—universities, libraries, and multiple government agencies. Coordination, funding, and digitization are the key efforts on which to focus.

A light at the end of the tunnel, which also has many concerned, is a budget allocation of over $40 million for a new facility, to replace Naylor Court. These more spacious days have allowed more funding, now the concern seems to be getting it right (this time). The promise (and threat) of more funding was pushed from the 2016 fiscal year budget to that of 2019 but planning funding remained. Simultaneously some internal reorganization is taking place in the Mayor’s office and the Secretary will report to the Office of the Senior Advisor (OSA) rather than directly to the Mayor. A request for proposals was issued, include a very extensive program: reception area (including meeting rooms and exhibit space), reference/reading area, storage for 90,000 square feet of records , records receiving area (loading dock), staff work areas (including processing space, conservation lab, meeting room, staff lounge).

On July 10, 2015 the Department of General Services (DGS) announced it had selected Hartman-Cox Architects and EYP of Washington, D.C. to design a new facility to house the District’s historic records.

“The selection of Hartman-Cox Architects and EYP of Washington, DC will allow us to continue to move forward with the design of the new Archives building, a facility that holds some of our most treasured historical documents. I look forward to seeing the designs unveiled as we continue this exciting journey that all of our residents can benefit from,” Mayor Bowser said.

The proposed 90,000 square-foot facility will provide the Archives with record storage space, preservation labs, research, exhibits, and space for public service functions.” (Note that the current facility is only 26,000 square feet.) The new Archives building will be designed to achieve, at a minimum, LEED–Gold Certification. Award-winning Hartman-Cox designed the recently opened George Washington University/Textile Museum, redesigned space in the National Archives and Smithsonian American Art Museum, and is working on rehabbing the historic 1785 Massachusetts Avenue NW.

Matthew Gilmore is the Editor at H-DC, a website which covers public humanities news and events in the District of Columbia. A link to Matthew’s webpage can be found here.