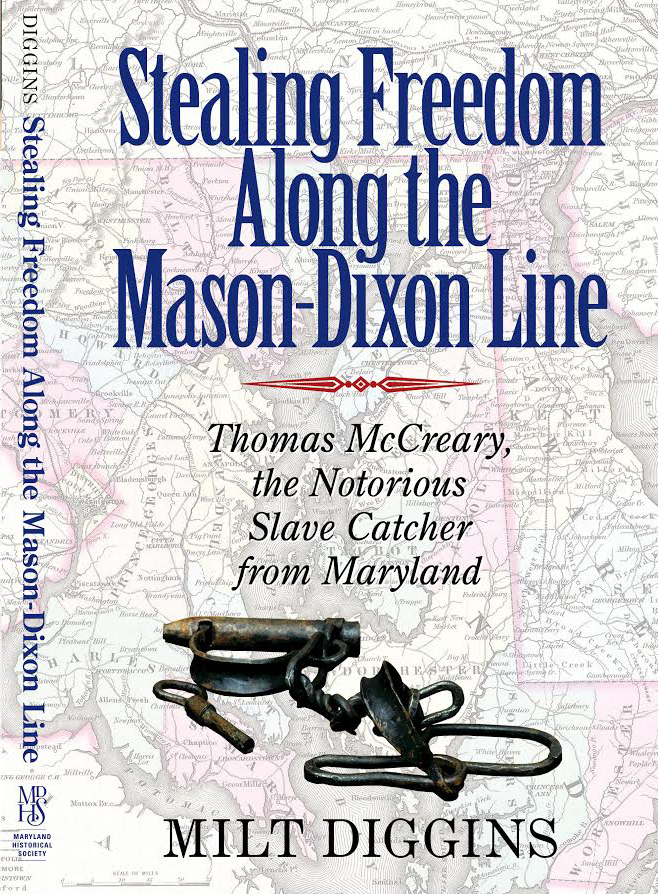

By Milt Diggins, author of Stealing Freedom Along the Mason-Dixon Line: Thomas McCreary, the Notorious Slave Catcher from Maryland

Stealing Freedom Along the Mason-Dixon Line: Thomas McCreary, the Notorious Slave Catcher from Maryland was published by the Maryland Historical Society. The narratives presented occurred in the Philadelphia–Wilmington–Baltimore corridor and offer a close-up view of slave catching and kidnapping that adds insight into how this issue contributed to the sectional hostility leading to Civil War. Prigg v. Pennsylvania; Pennsylvania’s personal liberty law of 1847; the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850; trials in Philadelphia, including the first two federal trials held in that city under the new fugitive slave law; the career of Philadelphia’s most notorious slave catcher, George F. Alberti; and the Christiana Riot and subsequent treason trial—all of these fold neatly into the story of Thomas McCreary and his community. Historians have noted a connection between the slaying of Maryland slave owner Edward Gorsuch in Christiana and the hanging of a witness against McCreary in Baltimore, but my research revealed additional significant connections between the treason trial and McCreary that had been overlooked.

Proslavery advocates insisted on their constitutional right to recapture accused fugitive slaves without restrictions in northern states. This interpretation lead to questionable arrests and kidnappings. African Americans who experienced the brutality, communities outraged by the incursion of slave hunters, and abolitionists openly opposed to slavery struggled for social justice. But stakeholders in the institution of slavery went to great lengths to protect the institution without qualms about their methods.

Frederick Douglass contributed the first question for the start of my investigation with a reference to “Thomas McCreary, the Notorious Kidnapper from Elkton.” I was at the Historical Society of Cecil County (Maryland) at the time. It was 2007, and I was the volunteer editor of the society’s publication. I regularly read through local newspapers in its collection in search of ideas for journal articles. I was skimming an 1852 newspaper when I came across the reference. Who was Thomas McCreary? Why did Frederick Douglass call him a notorious kidnapper? These were the obvious questions to start with and I expected to know the answers that day. All I needed to do was ask around at the society or check the files that were in easy reach. I was wrong. I would not have a quick answer. I ended up with more questions instead. Why is it no one at the historical society knew of McCreary? Why do the resources within easy reach make no mention of him, and for that matter, why is the McCreary family file missing?

But I had no reason to suspect Douglass’s remark would generate more questions, involve years of research, and turn into a book. I just started my research, when my interest was heightened by two academic researchers from Pennsylvania. Working on separate projects, they arrived at the society within months of each other, asking what information the society had on McCreary. One of the researchers was Chris Densmore, the curator at the Friends Historical Library at Swarthmore College. It was during conversations and email exchanges with him that I realized the potential scope of my research and how to frame it. Over time I would visit state and local archives and historical societies in Maryland, Pennsylvania, and Delaware and make full use of online resources.

I had decided to build the narrative outward, using Thomas McCreary and his community as the framework for examining the issue of slave catching and kidnapping. This unique approach enabled a closer view of multiple perspectives held by those caught up in the animosity and violence. The addition of McCreary’s community provided additional depth to the story. The local editors justified McCreary’s actions against charges from Pennsylvania and Delaware critics who questioned his arrests and condemned his kidnappings. It also highlighted a contrast with communities that were outraged by McCreary and others like him. In addition to a kidnapping by McCreary in Philadelphia and his name coming up at the treason trial there, residents from McCreary’s home county had connections with other events in Philadelphia. Several court cases in Philadelphia, including the first two Philadelphia trials under the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, involved accused fugitives from McCreary’s home county. Several of those court cases involved arrests by George F. Alberti, Philadelphia’s notorious slave catcher and kidnapper. While reading through secondary sources, I saw another reason for writing this book. Although a number of contemporary history books included the Philadelphia–Wilmington–Baltimore corridor in a broad survey of the slave catching and kidnapping issue, only one, Thomas Slaughter’s Bloody Dawn, took a close look at the region in his study of the Christiana Riot and subsequent treason trial. I had struck a rich, largely untapped vein of incidents and resulting reactions in the region. It was time for these stories to emerge from archival obscurity and be retold.

I had mentioned that I made use of a number of collections in Maryland and surrounding states, each of them worth the trip. I appreciated the resources available and the assistance received at each location. But I close in praise of the Historical Society of Cecil County (HSCC), not just because I had served on its board for fifteen years, but because of the unique opportunity it offered. It was the HSCC that provided the valuable starting point and enabled me to start constructing a history of the slave-catching issue from an original angle. Digging through its wealth of resources gave me an understanding of McCreary’s character, motives, and relationships, especially with the county’s political machine. The resources also revealed the political atmosphere in the community and its defense of their local hero, who was eventually elevated to state hero. With all the resources online and at the larger archives, it is important not to overlook the local sources. Many county historical societies, like the one in Cecil County, are operated by an all-volunteer staff, or they depend heavily on volunteers to serve the public.

The HSCC has an abundance of distinct source material, much more than the staff could ever hope to digitize and upload to its website, or to outsource on limited funds. Fortunately, as a member of the board, I literally had keys to the building, the alarm code, and unlimited access to the archives. I started by reviewing all the local nineteenth-century newspapers, gathering notes, and finding clues for searches beyond Cecil County. I searched through courthouse records that were recently added to the society collection while I was doing my research, looking for every reference to Thomas McCreary, his family, and others whose names appeared with McCreary, mostly people who were suing him to collect a debt. I pored over tax records. I looked for additional information on local residents McCreary associated with. I searched the minutes of county and town commissions. I searched the county records for the almshouse and the insane asylum and a variety of books in the society library that mentioned McCreary. The materials at the HSCC that could not be found online or housed at other archives provided an invaluable platform to build a regional story upon.

Whereas McCreary and his community were the framework for the story, I want to close with attention to the heart of the story–Elizabeth Parker, age twelve, and Rachel Parker, age seventeen, and their community. McCreary had kidnapped the Parker sisters about two weeks apart, claiming they were fugitive slaves from Baltimore. Their community knew the girls were not fugitive slaves. They responded with a heroic and compassionate effort to regain freedom for the sisters. One man, Joseph Miller, would lose his life in the pursuit of justice for Rachel. When Rachel and Elizabeth could finally make their plea for freedom, I described the community’s response as “one of American history’s greatest displays of humanity in the face of hostility.” The endurance of the Parker sisters under duress, the support, compassion, and courage of their community, and the pursuit of justice that cost Miller his life are the reasons I dedicated the book to all of them.

For more information on the book and my other ventures, please visit my website.

Milt Diggins is a retired educator, an independent historian, writer, and speaker. He holds a master’s degree in secondary education from Towson University, where he also had earned a degree in history. After his years in the classroom, he served on the Board of Trustees for the Historical Society of Cecil County for fifteen years and was the volunteer editor of Cecil County Historical Journal for eight years. He wrote numerous history articles for that publication and a local newspaper. In the summer of 2006, the Maryland Historical Magazine published his article about the political and engineering effort to construct the first railroad bridge across the mouth of the Susquehanna River. In 2008, Arcadia Publishing published his first book, Images of America: Cecil County, a photographic history of the county. In 2014, I researched and wrote about two Underground Railroad sites for the National Park Service’s program to verify and designate authentic UGRR sites. The sites were the Chesapeake and Delaware Canal and the Philadelphia, Wilmington, and Baltimore Railroad steamship ferry at the Susquehanna wharf and station at Perryville, Maryland.

Milt Diggins is a retired educator, an independent historian, writer, and speaker. He holds a master’s degree in secondary education from Towson University, where he also had earned a degree in history. After his years in the classroom, he served on the Board of Trustees for the Historical Society of Cecil County for fifteen years and was the volunteer editor of Cecil County Historical Journal for eight years. He wrote numerous history articles for that publication and a local newspaper. In the summer of 2006, the Maryland Historical Magazine published his article about the political and engineering effort to construct the first railroad bridge across the mouth of the Susquehanna River. In 2008, Arcadia Publishing published his first book, Images of America: Cecil County, a photographic history of the county. In 2014, I researched and wrote about two Underground Railroad sites for the National Park Service’s program to verify and designate authentic UGRR sites. The sites were the Chesapeake and Delaware Canal and the Philadelphia, Wilmington, and Baltimore Railroad steamship ferry at the Susquehanna wharf and station at Perryville, Maryland.