Estevan Rael-Gálvez, Senior Vice President of Historic Sites at the National Trust for Historic Preservation, delivered the 2014 Fredric M. Miller Lecture in Public History on May 8 at the Philadelphia History Museum. This is a slightly edited version of Dr. Rael-Gálvez’s presentation.

Buenas noches, good evening. Where I come from, before you even speak, before you lead into a conversation and tell a story, it is not only respectful but necessary to introduce yourself—to tell what people and place you belong to.

I was born at the edge of a very particular moment in time, in the midst of a civil rights movement, where the tenacious march of men and women thirsting for justice could only be matched by something as unworldly as someone walking on the moon. I was born into an ancient and sovereign geography of the Taos and San Luis valleys, along the Colorado and New Mexico border, surrounded by enormous sky and sacred mountains and raised in the smallest village you can imagine, on my parents’ farm. Like my father before me and multiple generations before him working and living in the same place, I grew up herding sheep and tending crops, the stewards of land and animals alike, solidifying a core set of values.

This eighty-seven-year old man—my father–always encouraged me to find words and stories as a way out, perhaps knowing that in spite of the fact that I had come from generations of farmers, my love of learning carried a promise for something else. As a complement, my mother, who spent decades schooling children in her own village, taught me how to use words and stories as a way in. Yet it was my grandmother who most inspired my imagination and encouraged my life-long hunger for memory. Once, while holding my hand in hers, she ran it gently against the grain of the ancient walls of her indigenous pueblo, revealing that I was also born into generations of people that belonged to those mud walls, to that mountain, and to that river that ran right through it, a place that Karl Jung in 1924 called the “roof of the American continent.”¹

This grandmother’s wisdom always inspired me to draw deeper still from the wells of memory, even from the broken histories, mine and those that I would encounter along the way, and to take those stories, center them, and raise them up. It is why I have always been drawn especially to the marginal stories, like those that I worked to recover in my doctoral work on the enslaved indigenous peoples of the Southwest—stories that have been quieted over the years by whispers as much as by silence, hushed aside even by those who have inherited them— carrying if not their geography in their faces and hands, certainly their memory in an aching consciousness. It is also the work that I am proudest of at the National Trust, working with such an inspiring group of individuals to recover the obscured and silenced stories.

I was fortunate to be raised in a place where its people, in spite of their marginalization, believed in the value of story and memory. Honoring these and other stories, my grandmother taught me that above all else, stories are gifts, but gifts always carry a great responsibility: to hold them, carry them, and recognize that balance is in knowing when they can be used to sustain community and when they can be used to raise its consciousness. But she also taught me that the most powerful gift is our imagination.

These are not the lessons learned from academia. I believe that being a public scholar requires of me the knowledge that the past holds a great deal of power. How the past is imagined, remembered, and memorialized is also subject to power, who holds it and who doesn’t. Our job as stewards of the past is to brush history against the grain, knowledge against power, and above all to find ways to create openings for dialogue and understanding. In this I draw from the profound vision of one of my favorite writers, Eduardo Galeano, who has stated, “I am not a historian; I am a writer, an educator who would like to contribute to the rescue of the kidnapped memory of all America.”²

I appreciate being able to begin in this way because I understand that our past shapes us, even in ways that we don’t always understand. I feel in my bones and blood that this is true, and I do believe that there is something deeper that propels us forward or holds us back, but in this knowledge, I recognize that we are also what we do, especially what we do to change what we are.

I also preface with my subjectivity because it informs my work and the way I move through the world. Positioning myself is cultural, but it also reflects my training. As an anthropologist, I learned how essential it is to be conscious and reflective of where I stand vis-à-vis what and whom I study. What we all bring to our work – experiences, knowledge, and perspective – matters. I have always found it peculiar that so many historians seem uncomfortable acknowledging their subjectivity, moving past feigned notions of being objective. Michel Foucault has noted that “historians take unusual pains to erase the elements of their work which reveal their grounding in a particular time and place . . . the unavoidable obstacles of their passion.”³

Beyond my personal introduction, it is perhaps even more essential to pull back the layers and acknowledge the ground beneath us. Back home, Pueblo people often say, “Wherever we go, we leave our breath behind us”—an invocation recognizing those who came before us and that remain with us, long after they have gone. Toward this end, let me acknowledge the Lenni Lenape (also known as the Delaware), the indigenous people who were once here, the people of Coa-quon-nock—the land of tall pines—first peoples of this place we now call Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Where I stand today in Philadelphia, I cannot help but think of the Revolutionary War, which is often constructed (or at least remembered) solely in stark terms of British and American forces, but in fact impacted many American Indian nations east of the Mississippi River. The Lenni Lenape were subject not only to this war, but to the region’s settlement as a whole—a violence over the land that should not be forgotten. I think of these losses, of both life and wisdom, when in 1782, those Lenni Lenape living on Smokey Island near Pittsburgh were attacked by Americans. In the confusion of the attack, the wampum belts and bark-books containing the tribal archives were lost in the river forever. There are no words for this loss, and yet, like a story from the Lenape of a lost boy who become a part of the spirit of the water, so too perhaps did these belts, these books flow into something, to be drawn upon later.

Whenever I think about story and place and about the importance of breath and life, I cannot help but evoke Archytas, who, commenting on Aristotle’s Categories, first wrote about “place as the first of all of beings, since everything that exists is in a place and cannot exist without a place.”? The very notion of place being characterized as the “first of all beings,” means that places are alive and meant to breath and thus meant to evolve. In so many ways, this is the perfect evocation of Philadelphia, a place that has always moved forward, but also a place so profoundly etched into the American narrative and consciousness, where tolerance, revolution, and liberty have for so long reflected the delicacy and strength of both a nation and a people evolving. But lest it be forgotten that democracy and freedom are delicate, I think of the fracture in the iconic Liberty Bell, a reminder perhaps that our work on these ideals will never be completed. The fissure reminds me that some Navajo craftsmen and women deliberately put an imperfection in their textiles, often called a spirit line. This conscious flaw gives the weaver a way out, but also a reason to continue making work.

It is important to recognize, however, that the antithesis of an ongoing process is one that is static, unchanging, and largely imagined. As a way into this evening’s lecture, I would like to use a framework drawn from the political theorist Benedict Anderson in his book Imagined Communities—a powerful work on nationalism, on what it means to belong to a nation, what it even means to define nation and how that happens.? He posits that communities are to be distinguished not by their falsity or genuineness but by the style in which they are imagined. Although writing about a different place, time, and people, Anderson’s work has resonated with me for years, particularly because I have long been interested in how the United States as a nation is represented, narrated, and even imagined as a place constituting a group of people who share, or imagine (perhaps even insist) that they share (or must share), a single historical experience, a single language, a single set of symbols, and a single ethnic origin.

One major component of Anderson’s work is that maps, censuses, and museums—all once defined as institutions of power—also “profoundly shaped the way in which the colonial state imagined its dominion—the nature of the human beings it ruled, the geography of its domain and the legitimacy of its ancestry.”? For our conversation this evening about history and memory, politics and power, I believe this tripartite framework of maps, censuses, and museums offers us a point of departure, and I hope to trace my preliminary thoughts about how each of them has been formative of a national narrative and consciousness in the United States, both real and imagined.

Maps

Let me begin first with maps, geographic representations of place that have served as essential tools to help people define, explain, and navigate their way through the world. I have long been fascinated by maps, perhaps because they are intricately tied to the origin of writing and to the artistic practice of placemaking. I think of the earliest maps, which were not of earth but of the skies, drawn on caves as early as 16,500 years B.C.E. I think of the Babylonian maps of clay and of the Chinese maps of wood; and I think of the first time someone made a map so that his or her community would not be forgotten to the ages.

But map making has also long been about ideology, politics and power—positioning places, people, and objects in space; lines on parchment that are often made at the behest of distant popes, kings, and presidents; acts that are part and parcel of empire making; imagining a community, so as to conquer and control it.

I think of the mappae mundi, the Christian maps of the world, less geographical descriptions than religious polemics and instruments of morality, consciously positioning certain places and spheres at the physical center or top of the world, while marginalizing, even demonizing others. I think of how Ptolemy’s maps would become central to the age of exploration, even his miscalculation of size and scope, a mistake that ironically perhaps emboldened explorers like Columbus, who may never have ventured as far as he did had he known the true distance.

The conceit of discovery and a manifest sense of supremacy, if not a product of mapmaking, would nonetheless greatly impact when, how, and why exploration would take place. It would define how the world would be divided, what nations in Europe would arrive on this continent first, and how these exploits would impact the early makings of the United States of America.

A replica of a map from the British Museum has hung in my offices for years, a reminder of how legend can instigate a journey and a journey can become exploration, a foothold of colonialism. The legend held that when the Moors conquered Mérida, Spain (an important center of culture founded by the Romans) in 1150, seven bishops fled the city with its religious relics. Accordingly, these bishops founded cities in far away lands, including those that would become known as Quivira and Cibola, two of the mythic Seven Cities of Gold in New Spain. In the late 1500s, long after Francisco Vasquez de Coronado had explored the Southwest looking for these cities of gold, John Martines, a Mallorcan, perhaps more storyteller than political cartographer, would create this map, depicting these seven cities and a region of the Americas—now part of the U.S.—that was about to be settled by Spaniards.

Not all maps were drawn at a distance, however. The dominion over land and people was highly dependent upon the acquisition of knowledge, and cartographers were a necessity for this end, often surveying and then representing how they saw the physical world. I think of Thomas Jefferson, the son of a land speculator, surveyor, and mapmaker. Unlike many of his contemporaries, Jefferson did not see the American West as empty wilderness, but recognized instead the reality—conflicting nations, all with claims of sovereignty. While president, Jefferson successfully acquired the Louisiana Territory from France in 1803 and at the dawn of the nineteenth century sent Meriwether Lewis and William Clark on an expedition up the Missouri River to the Pacific Ocean to explore and map the region—a venture that everyone here will know was so intricately tied to Philadelphia, conceptualized, designed, trained for, equipped, and finally memorialized here.

The maps produced by the Lewis and Clark Expedition depict a vision of lands to be conquered and acquired, as well as ideals of how places should be settled. Rolling out a map often demonstrated authority and knowledge as well as the imperial imaginary. What if displacement, rather than settlement were a frame of analysis? What would that map look like and how could these maps, all in juxtaposition, support an elevation of consciousness? What would a map that shows the massive shift of peoples from Africa to the Americas look like? What would a map that shows the gradual, massive depopulation (or even the survival) of indigenous peoples in the United States, if not the entire Americas, look like? Displacement is certainly one of the formative experiences underlying human history, and its centrality in the formation of the United States is no exception.

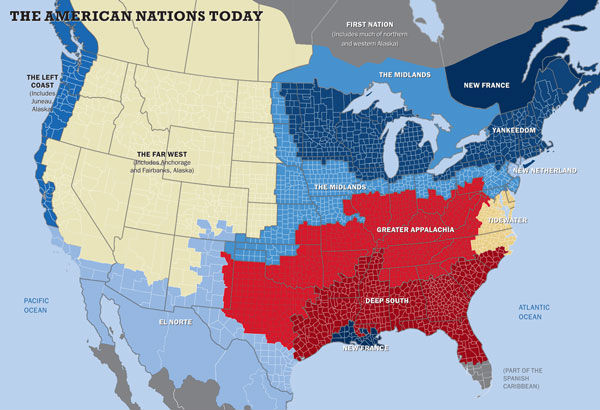

Speaking of both the formation of the U.S. as well as the possibilities of remapping, Colin Woodard’s American Nations: A History of the Eleven Rival Regional Cultures of North America offers a fresh insight: we are not one single nation, he argues, but actually a federation of eleven regions, each with its own distinct history, ethos, religions, politics, and ethnographic characteristics. “For generations,” he notes, these distinct regions “developed in remarkable isolation from one another, consolidating values, practices, dialects and ideals” often in contradiction with the other.?

Woodard carefully traces the unique settlement and gradual development of each of these regions, impacted by competition with rival European countries vying for land, which meant power and by events like the American Revolution, the Civil War, the Mexican-U.S. War, and the Spanish American War. I think about the impact of this last war, an imperial reach by the U.S. against Spain, on the mid-Atlantic region, for it incorporated Latinos into the nation, not just the island of Puerto Rico, which became a U.S. territory as a result of the war, but its people, whose migrations into places like New Jersey and New York have transformed these places, historically and into the present.

Woodard also assesses how certain regional values have affected our nation’s development, how, for example, the profound tolerance of diversity and commitment to freedom of inquiry characteristic of the region of New Netherlands resulted in the development of the Bill of Rights, a development, he argues, that would never have come from the Tidewater or Greater Appalachia regions. These distinct regions even cross international boundaries into Mexico and Canada, and though the author does not emphasize it, across multiple indigenous and sovereign communities.

Woodard argues too that how state boundaries were drawn, though subject to the politics of placemaking, failed to capture accurately what these regional differences reflect. For instance, Pennsylvania, according to Woodard, is actually composed of “the Midlands,” “New Netherlands,” and “Yankeedom,” each of which has a unique development. He argues that the Midlands, which extends westward from Pennsylvania, is perhaps the “most American of nations,” as, like Pennsylvania in the eighteenth century, it welcomed people from many different nations and creeds.

What I believe is most important in Woodard’s work is not solely that it disrupts our view of the nation and encourages an imaginative remapping, but that it recovers what is essential in each of these regions. Understanding the particular roots, experiences, and shifts of these regions is critical to understanding U.S. and continental history better. This is especially clear to me coming from a region whose history still does not figure in any meaningful way into the national narrative, let alone the consciousness of this nation—imagined still as foreign perhaps because it was acquired through war and conquest—but the reality is that with the people and land also came their particular stories and memories.

As I think about the fact that maps are geographic representations of space, I think also of real three-dimensional maps—a true cartography connecting people, place, and story. Artists and poets perhaps give us the best ways to re-imagine how space defines us as much we have defined it. But I also think of the Mohawk ironworkers who, throughout the twentieth century, risking their lives, would play an important role in building the skylines, not only of New York City, but Detroit, Chicago, and Philadelphia as well, leaving a lasting impact on our urban landscape. When you look up to these skyscrapers, think of these skywalkers, whose people, once displaced, became a part of a new cartographic project.

Censuses

Like maps, I love censuses, perhaps because as a graduate student and beyond, I have spent countless hours excavating these particular documents, attempting to piece together from them fragments into whole lives, like shards into clay pots, and from those whole lives, families and communities. I have probably laid my eyes on every single census record in New Mexico from the accounting of the first Euro-mestizo colonists enumerated in 1598 through the three colonial rules of Spain, Mexico, and the United States, ending with the 1940 U.S. census, the most recent to be released.

Censuses may not be so old as those efforts to decipher the sky, chart distance, and record visual presence, but the effort to enumerate individuals is perhaps as old as the development of cities. The Babylonians undertook what is perhaps the first census in 3800 BCE, nearly six thousand years ago, though the oldest existing census comes from China, completed in the year 2 A.C.

Although maps functioned in some way to depict settlement, the documents that illustrate these holdings and their meaning most vividly are found in the apparatus of the colonial census. The information that a map carried topographically, the census could accomplish ethnographically, and like a map, censuses contributed to the production of knowledge and ultimately how the empire imagined its domain.

I have worked in archives throughout my career, and though I have always recognized the power of documents to recover stories, I also am keenly aware that a colonial archive developed as part of the extension of empire. The colonial archive, of which census documents are a part, has served as a technology of imperial power, conquest, and hegemony. Foucault would rightly point to the colonial archive as a “monument to particular configurations of power” and to much of what is contained therein as “documents of exclusion.”?

As a colonial studies scholar, I have also always recognized that like any record, censuses contain silences, but in my reading of them over the years, I have always been most interested in how they reflect, construct, and perhaps erase and obscure identity, including race. In the colonial context, how a person was labeled could determine levels of punishment. It could open or close down possibilities for marriage and where you could live. At the same time, the criteria used to determine who belonged where underscored the permeability of boundaries, opening possibilities for assertion among interstitial groups of “mixed-bloods.”

I am reminded here of a letter sent by a distinguished bard to officials in New Mexico in 1883, regretfully declining an invitation to participate in an anniversary event in Santa Fe but sharing a few words off hand, a portion of which I excerpt”

We Americans have yet to really learn our own antecedents, and sort them, to unify them… we tacitly abandon ourselves to the notion that our United States have been fashion’d from the British Islands only, and essentially form a second England—which is a very great mistake. Many leading traits for our future national personality, and some of the best ones, will certainly prove to have originated from [something] other than British stock.?

Walt Whitman goes on to speak about the necessity of acknowledging both the “Spanish” and indigenous peoples of our nation and therefore as a part of the United States. But I am most fascinated by this early counterpoint to the presumed identity of the United States, an essential point made by Woodard and others. Yet the narrative and consciousness of who the people of the United States are still remain as much now as in 1883 rooted in a static, distorted, and imagined identity. Not even the populations of the thirteen original U.S. colonies were as homogenous as the pervasive image reflects still. They were English, Cherokee, African, German, Sephardic Jew, Scottish, Iroquois, French . . .

During the sixty years that New Mexico fought for statehood, Congress pronounced on countless occasions that mestisaje, hybridity, was the major objection to including the people of New Mexico as citizens of the United States. Aside from the blatant racism of this view and the fact that New Mexicans were denied full citizenship for over half a century, the failure to comprehend the strength rather than adversity of mixture is searing. The reality, however, was that mixture is truly at the heart and foundation, not just of places settled by Spain and France, but also of the entire United States, which in part we know thanks to the work of Gary Nash, who was the first Miller Lecturer and who has worked hard to excavate, in his words, the “the hidden history of mestizo America.”¹?

More work needs to be done to understand the nation, and tracing the categories of race into the U.S. Census from 1790 to 2010 can offer a fascinating narrative, one that reveals not only how the U.S. has been imagined, imagined itself—but to the point, how race is perceived and constructed. To trace our fingers along this jagged edge exposes how people were counted or not; and how the nation perceived personhood early in the republic (i.e. counting the enslaved as only three-fifths of a person).

Initially, in spite of the mixture, the U.S. Census only counted Americans as either white or black, with blacks classified as either free or slave until 1860. Over time, the United States has also added some other racial categories. Asian American and Native Americans categories were added in 1860. However, the first census to enumerate all Native Americans occurred in 1890, and while some earlier tribal rolls exist, those living on reservations were not counted in the census before 1890. Also, between 1850 and 1870, and in 1890, 1910, and 1920, mulattoes were enumerated, along with other castes, such as quadroons and octoroons.

The narrative thread of Latinos in the U.S. Census is also interesting. In 1930, Mexicans were counted as a separate race for the first time, which spawned a fascinating debate about whiteness within and outside of this community. It was not until 1970 that Latinos were enumerated as a distinct group, a practice that has continued in every census since then. That same year the Census Bureau also began offering Latinos several sub-group options with which they could choose to identify, such as Mexican, Puerto Rican, and Cuban. Major shifts occurred when the “Other” racial category was added in 1950 and the “Multiracial” category in 2000, finally acknowledging hybridity.

Undeniably, the U.S. census has been about colonizing, categorizing, and constructing race, nation, and community, but can’t it also be about catalyzing and raising consciousness? Imagined as this construct may be, the bureaucracy of censuses has also reflected that we are not a homogeneous community, demonstrating that demographic shifts in the U.S. continue as they always have. While some parts of the country may not have seen these changes so much as others, the presence of Latinos in particular is notable: the 53 million Latinos across the U.S. have become the nation’s largest ethnic or racial minority. Sixteen states have at least half a million Latino residents, including New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Massachusetts. Latinos make up 6 percent of the population of Pennsylvania, with 750,000 individuals; in New Jersey, 1.6 million Latinos comprise 18 percent of the population; and in New York, with 3.5 million Latinos, 18 percent.

These numbers and the data that have gradually emerged from the need to count and be counted tell a remarkable story. While 6 percent seems small, these numbers will escalate, and it will be imperative for cultural and historical organizations to find ways to respond to, to engage, and to include this population. It is an interesting population, however, for the U.S. to begin engaging. The question is really how, especially since it has been so largely imagined in a particular narrative. Arguably, it has served the nation’s purposes historically to imagine Latinos as uneducated and illiterate, justifying exclusion and exploitation. In the present, it serves the nation to imagine Latinos as “illegal,” with illegitimate claim to membership in society. The reality is that as Latinos, we represent not only a deep and old historical presence in this place we now call the United States, but the most recently arrived—all of our stories—matter.

The question is one of being and belonging to a nation and of being counted. The various Latino communities are at the center of this struggle over who belongs, and not simply because of our growing numbers but also because of the complexity of our biological, cultural, economic, political, and social makeup. Perfecting our union, as President Barack Obama has reminded us, requires not only recognizing difference and diversity. It is at the heart of who we are, in spite of the bureaucratic mechanisms that have flattened this story. Responding to this imperative requires reflecting instead the beautiful dimensions of this nation’s complexity. What the census cannot capture, I believe those of us who work within the cultural realm can. We pull back the layers and tell who we are, whole.

Museums

Let me turn now to museums, the third of Anderson’s tripartite framework, thinking of how they functioned (and perhaps still do) to imagine a community and the nation. My love of museums has been a gradual journey. For many years now, I have been honored to administer museums—to support and realize how important they can be to our communities, consciousness, and creative potential.

But where and how I grew up, there was not the opportunity to visit a museum. None was in close proximity to where I lived, and even if there had been, I don’t believe there was an inclination in my family or perhaps even culture to have visited it. I don’t want to lose this point, since I do think as stewards of culture, particularly in museums, we need to explore issues of access and, perhaps even more importantly, interrogate issues of relevance, reflect on ways to support broad engagement, and do better! Exploring this has been an imperative that has defined all of my work with museums over the years, and I believe requires raising the critical questions and boldly addressing the existing tensions.

If a map points to where and a census points to whom, then the museum captures, I believe, the what, how, and why. The possibility of what a museum can be is actually carried in the word that tells us what it is. Etymologically, the word museum comes via Latin m?s?um, meaning “library” or “study;” and from Ancient Greek, µ???????, mouseion, ”place devoted to the muses.” As the Babylonians were among those who first mapped their community and then enumerated it, the Ennigaldi Nanna’s museum, dating to circa 530 BCE, is the first museum known to historians. The curator was Ennigaldi, the daughter of Nabonidus, the last king of the Neo–Babylonian Empire.

Nanna’s museum is like all early museums, begun as the private collections of wealthy individuals, families, or institutions gathering art, curious natural objects, and artifacts. This is certainly true of one of oldest museum in the United States, founded here in Philadelphia in 1773. I could barely tear myself away this week from learning more about Charles Willson Peale and the birth of the Philadelphia Museum, which he began by collecting artifacts and displaying them in his own home. He also painted portraits of patriots of the American Revolution and collected those painted by others. As many in this room probably know better than I, he not only founded the museum but can be credited for creating the museum system that we know today in this country.

However, it is so important to bring a critical reading to the development of this original museum—it remains essential to continue to recover the stories of those objects that were collected in his museum. Peale’s initiative reflects an amazing project of national imagining. I don’t think that it is a coincidence that it emerged at the particular moment in U.S. history that it did and here, in Philadelphia, reflecting not only the drive to experiment and enlighten, but also the formation of our national narrative itself. Peale’s acquisition, for example, of a mastodon specimen discovered near Newburgh, New York, not only reflected popular interest in natural history, but also was a subject that the likes of George Washington and Benjamin Franklin had written about and discussed. A friend to Peale, Thomas Jefferson, in his Notes on the State of Virginia, would use the evidence of the mastodon to directly counter existing theories that the “new world” did not and could not support the flora, fauna, and other life that existed in the old world,. The mastodon for Jefferson and others became emblematic of a new, better, and powerful nation on the hill.

Beyond mastodon bones, however, I am more curious about the American Indian objects that became part of the collection. Writing about the objects amassed during the Lewis and Clark Expedition that ended up in both Jefferson’s “Indian Hall” at Monticello and in Peale’s museum, Castle McLaughlin argues that these objects should not be seen as products of collecting in an anthropological sense, but as results of exchanges made in diplomatic and social contexts.¹¹ McLaughlin is right; however, the larger point is that those exchanges—which should recognize the agency of indigenous peoples— were part and parcel of the extension of U.S. imperialism. While the development of museums created a new encounter between different constituencies, those encounters were not equal. The very removal of material from imperial territories to display, represent, and market is illustrative of imagining a community, but toward a particular end. It was not surprising for me to learn that in the 1840s when Peale’s museum closed its doors and the objects sold and disbursed, one of the buyers was the ultimate showman of the national imaginary, Phineas T. Barnum.

Whether the Smithsonian Institution or Peale’s Philadelphia Museum, U.S. museums are not exceptions to how any global museum developed in a colonial and bureaucratic context. John MacKenzie, in his Museums and Empire: Natural History, Human Cultures and Colonial Identities, argues that the essentially European phenomenon of the museum played out in colonized lands, as these new museums developed imperial, national, and local forms of identity, whether exclusive or inclusive.¹² In this way, museums, like monuments, formed in the body politic and developed as national symbols, demonstrations of wealth and power.

It is important to know these origin stories for several reasons. It is the historical context within which many people, including indigenous people, know and think of museums. It is important to address the historic inequities in whatever way we can. Returning objects to where they can rest peacefully is powerful, and I am fortunate to have participated in initiatives that have worked toward repatriation. It is also important because knowing allows us to point toward new practices of collecting, displaying, and interpretation.

As I think of other counterpoints to traditional practices and the possibilities in museums, I also think of Orhan Pamuk, the gifted Turkish writer, Nobel Laureate, and director of Istanbul’s Museum of Innocence. In his “Modest Manifesto for Museums,” he argues that the “measure of a museum’s success should not be its ability to represent a state, a nation or company, or a particular history. It should be its capacity to reveal the humanity of individuals.” If, as Pamuk concludes, the future of museums is “inside our own homes,” what does this look like, how does it change imaginative possibilities?¹³

Conclusion—A Decolonial Imaginary

I hope that I have shown how imperative it is to understand how the map, census, and museum were not only instruments of empire, creating a particular ideology and grammar, but when applied to space, place, and people, shaped an image of the nation—an imagined community, as Anderson phrased it. This may be true in the development of any nation-state, and the United States is certainly no exception. It is important to understand that this illusion of world-making, especially in the context of colonialism and imperialism, is much more than knowledge and rule. It also represents actual violence upon the land as well as epistemic and discursive violence. I believe that my use of Benedict Anderson’s imagined community theory and tripartite framework is not only about elevating consciousness about what happened here, but is also a practical step towards reimagining new possibilities.

Maori scholar Linda T. Smith has cogently observed that “transforming our colonized views of our own history (as written by the West), however, requires us to revisit site by site, our history under Western eyes.”¹? Similarly, in her work to recover Latina histories, Emma Perez uses the term “decolonial imaginary” as a way of overcoming a colonial past, by literally reinscribing new possibilities. The decolonial imaginary¹? demands that we create a new cartography, a new way of recording presence, and a new way of remembering ourselves whole. This counterpoint, this turnaround lies in our ability to creatively imagine the future, to ground our work in the communities and networks that are core to our sites, our organizations, and our classrooms—spaces that are changing all around us—and by this, raise critical consciousness about why history matters.

When I think of decolonization, I think of the opportunity to pull back the layers, recover lost stories, interrogate the mythologies, and provide a chance for new stories to emerge. In between, we will find beauty and joy, tragedy and pain, but through it all, this work is critical and necessary because it is also about what it means to navigate our human ties in the midst of what is deeply contested. Once we are able to move past the inaccurate notion that we share (or ever did share) a single historical experience, ethnic origin, language, religion, or even a single set of symbols, we might begin to appreciate the depth and breadth of what is actually all around us.

Deconstructing power while simultaneously nourishing and sustaining culture requires this deepened understanding, as well as inspired reimagining. We have the responsibility to awaken memory, knowledge, and will and to expand the depth and breadth of our national narrative and consciousness. From my title, I am sure that my hunger for memory is obvious, and the thirst for justice, if not so obvious, should be—it is about imagining what our work might look like if we applied the ideals of social justice to the practice of history. In this imagining, every story is worth remembering.

There are many challenges before us as a nation, but I stand confident in the possibilities that lie ahead, knowing that the enduring legacy of our communities should be that we took responsibility for the thinking that had been handed down to us; that we reimagined the promise of our humanity; and because of our work, that we changed the world to be a better place for those that follow us.

Estevan Rael-Galvez is Senior Vice President of Historic Sites at the National Trust for Historic Preservation. Prior to this position, he served as executive director of the National Hispanic Cultural Center in New Mexico, as the state historian for New Mexico, and as chair of the New Mexico Cultural Properties Review Committee. He received his Ph.D. in American cultures from the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor.

The annual Miller Lecture, sponsored by the Mid-Atlantic Regional Center for the Humanities at Rutgers-Camden, recognizes the late Fred Miller’s pioneering work as an archivist and public historian to preserve and promote the history of Philadelphia, where he directed the Urban Archives at Temple University; and of Washington, D.C., where he worked at the National Archives and Records Administration. This year’s lecture was cosponsored by the Pennsylvania Humanities Council, the Center for Public History at Temple University, Taller Puertorriqueño, and the New Jersey Council for the Humanities.

Notes:

1 C.J. Jung, Memories, Dreams, Reflections (New York: Random House, 1965), 251.

2 Eduardo Galeano, Genesis: Memories of Fire, trans. Cedric Belfrage (New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 1998), xv.

3Michel Foucault, “Nietzsche, Genealogy, History,” in Language, Counter-Memory, Practice: Selected Essays and Interviews, ed. D. F. Bouchard (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1977), 156-7.

4 Quoted in Edward Casey, Remembering: A Phenomenological Study (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1987), 184.

5 Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism (New York: Verso, 1983).

6 Ibid, 168.

7 Colin Woodard, American Nations: A History of the Eleven Rival Regional Cultures of North America (New York: Viking, 2011), 2.

8 Carolyn Hamilton, Vern Harris, and Graeme Reid, “Introduction,” in Refiguring the Archive, ed. Carolyn Hamilton, Verne Harris, Jane Taylor, Michele Pickover, Graeme Reid and Raizia Saleh (Cape Town: David Philip, 2002), 8.

9 Walt Whitman, “The Spanish Element in Our Nationality,” in Prose Works (Philadelphia: David McKay, 1982); Bartleby.com, 2000; at www.bartleby.com/229/.

10 Gary B. Nash, “The Hidden History of Mestizo America,” Journal of American History 82, no. 3 (December 1995): 941-64.

11 Castle McLaughlin, Arts of Diplomacy: Lewis and Clark’s Indian Collection (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2003).

12 John MacKenzie, Museums and Empire: Natural History, Human Cultures and Colonial Identities (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2009).

13 Orhan Pamuk, “A Modest Manifesto for Museums,” American Craft Magazine (June/July 2013); at http://craftcouncil.org/magazine/article/modest-manifesto-museums.

14 Linda Tuhiwai Smith, Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples (London: Zed Books, 1999), 34.

15 Emma Perez, The Decolonial Imaginary: Writing Chicanas into History (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1999).